1. El Niño

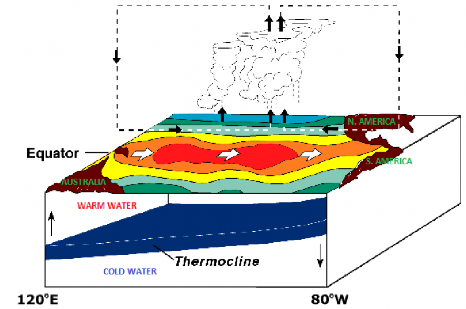

Near the end of each year as the southern hemispherical summer is about to peak, a weak, warm counter-current1 flows southward along the coasts of Ecuador and Peru in the eastern equatorial Pacific Ocean, replacing the cold Peruvian current (an eastern boundary current along South America). In the past, local residents referred to this annual warming as “El Niño,” (Spanish: meaning “The Boy Child”) due to its appearance around the Christmas season. For Peruvian fishermen, it signifies the end of the fishing season. Normally, these warm counter- currents last for at most a few weeks when they again give way to the cold Peruvian current.

However, every three to seven years, this counter-current is unusually warm and strong. It lasts for several months and is often accompanied by heavy rainfall in the arid coastal regions of Ecuador and northern Peru. Over time the term El Niño began to be used in reference to these major warm episodes.