Moral philosophers often discuss two separate but interrelated aspects of morals. These are (1) action or intention and (2) how or why an act is done. Consider the following moral maxims:

Live in peace with your neighbours; Tellthe truth;

Aim at the greatest happiness of the greatest number.

These maxims ask people to do or intend some definite act. Now, consider the following moral maxims:

Be conscientious; Be pure in heart.

These two maxims emphasise a type of attitude that can accompany a variety of acts.

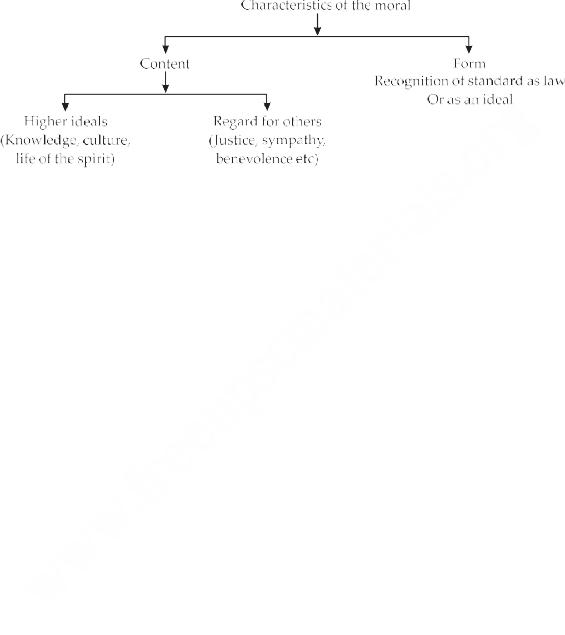

Moral judgments take into account both what is done or intended, and how or why the act is done. Old textbooks of Ethics refer to the first aspect as the ‘matter’ or ‘content’ of the moral; and to the second aspect as the ‘form,’ or the ‘attitude’ of the moral.

Moral Judgements based on Content

Moral judgements, based on the content of morals, are based on two points of view – (1) ‘higher’ and ‘lower’ within the man’s own self; and (2) his treatment of others. The first perspective contrasts a life of the spirit to the life of the flesh, the finer to the coarser, and the nobler to the baser. These two opposite tendencies are parts of human nature. Without the instincts for aggression, self-preservation and procreation, human beings would have perished. But in order to realise their full potential, men have to control these impulses andpassions by other motives. Men can make thebest of their (rational) life only by pursuing higher or ideal interests through a process of mental and moral discipline.

The second point of view for making moral judgements based on the content of morals relates to the treatment of others. In this conception, qualities like justice, kindness, and the Christian golden rule (Behave towards others as you would like them to behave towards you) are the right and good. Injustice, cruelty, selfishness are the wrong and the bad. These opposing qualities are known as virtues and vices.

Moral Judgements based on Form or Attitude: the Right and the Good

When we describe conduct as right, we judge it. We look at the act with reference to a standard, and evaluate the act. We regard this standard as a ‘moral law’ which we ‘ought’ to obey. We honour its authority. We consider the standard as a check on our impulses and desires. Conscientious men are those who recognise such a law and do their duties.

When we consider conduct as ‘good’, we approach it from the standpoint of value. We are thinking of what is desirable. This is also a standard, but it is a standard regarded as an end to be sought rather than as a law (to be obeyed). Moral agents have to ‘choose’ it and identify themselves with it as an ‘ideal’. The conscientious man, viewed from this standpoint, would seek to discover the true good, and to follow ideals, instead of following impulses or accepting any seeming good without careful consideration. As he is guided by ideals the good man will be straightforward and sincere: that is, he will not be moved to do the good act by fear of punishment, or by bribery, just as the upright man will be ‘governed by a sense of duty,’ of ‘respect for principles’. We can show these two types of the moral as in the following table.

There are many ends which men may pursue in life. Some may seek wealth, independence, power, fame, knowledge, love, excitement or peace. Others may take interest in art and science; or in loving and serving others; or in development of social and political institutions. Some others pin their highest hopes on a life beyond death. The different ends men pursue lead to a question: Is there some ultimate ideal of life or some standard of judgment which enables one to say that one form of conduct is better than another. From this angle, Ethics is seen as a study of the ideals involved in human life.

Ethics is concerned with practical life and not merely with pure theories. It is normative and lays down rules or laws for defining ideal conduct. Ethics is not concerned only with the facts of the moral life but deals with the rules and ideals of the moral life. The former study is a part of sociology which deals with the general structure of societies. The latter study is Ethics. Sociology is a positive (or descriptive) science; Ethics is a normative (or prescriptive) science. But, of course, in dealing with Ethics, we cannot ignore morals which societies actually follow. In administrative contexts, approach to Ethics has to be practical. It has to be normative or rule-based dealing with real life administration and not with moral games or puzzles or abstract theoretical systems.