12 Modern Painting

Nomenclatures are not always irrelevant, for example, the term 'modern'. It may mean many things to many persons. So also the term 'contemporary'. Even in the field of the fine arts there is confusion and unnecessary controversy among artists, art historians, and critics. In fact, they all really have the same thing in mind and the arguments hover round terminological

implications only. It is not necessary here to indulge in this semantic exercise. Roughly, many consider that the modern period in Indian art began around 1857 or so. This is a historical premise. The National Gallery of Modern Art, New Delhi covers its collection from about this period. In the west, the modern period starts conveniently with the Impressionists. However, when we talk of modern Indian Art, we generally start with the Bengal School of Painting. Both in the matter of precedence and importance, we have to follow the course of art in the order of painting, sculpture, and the graphics, the last being comparatively a very recent development.

Broadly speaking, the essential characteristics of the modern or contemporary art are a certain freedom from invention, the acceptance of an eclectic approach which has placed artistic expression in the international perspective as against the regional, a positive elevation of technique which has become both proliferous and supreme, and the emergence of the artist as a distinct individual.

Many people consider modern art as a forbidding, if not forbidden, territory. It is not, and no field of human achievement is. The best way of dealing with the unfamiliar is to face it squarely.

All that is necessary is will, perseverance and reasonable constant exposure or confrontation.

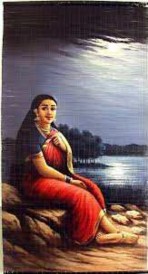

Towards the close of the nineteenth century, Indian painting, as an extension of the Indian miniature painting, snapped and fell on the decline and degenerated into feeble and unfelt imitation largely due to historical reasons, both political and sociological, resulting in the creation of a lacuna which was not filled until the early years of the twentieth century, and even then not truly. There was only some minor artistic expression in the intervening period by way of the 'Bazar' and 'Company' styles of painting, apart from the more substantial folk forms which were alive in many parts of the country. Then followed the newly ushered Western concept of naturalism, the foremost exponent of which was Raja Ravi Verma. This was without parallel in the entire annals of Indian Art notwithstanding some occasional references in Indian literature of the idea of 'likeness'.

An attempt to stem this cultural morass was made by Abanindranath Tagore under whose inspired leadership came into being a new school of painting which was distinctly nostalgic and romantic to start with. It held its way for well over three decades as the Bengal School of Painting, also called the Renaissance School or the Revivalist School - it was both. Despite its country-wide influence in the early years, the importance of the School declined by the 'forties' and now it is as good as dead. While the contribution of the Renaissance School servedPainting as an inspired and well intentioned if not wholly successful link with the past, it has had little consequence even as a 'take off ground for the subsequent modern movement in art. The origins of modern Indian art lie elsewhere.

The period at the end of the Second World War released unprecedented and altogether new forces and situations, political as well as cultural, which confronted the artist, as much as all of us, with an experience and exposure of great consequence. The period significantly coincided with the

independence of the country. With freedom also came unprecedented opportunity. The artist was set upon a general course of modernization and confrontation with the big, wide world, especially with the Western World, with far-reaching consequences. Too far removed as he was from Indian tradition and heritage and emotionally estranged from its true spirit, he absorbed the new experience eagerly too fast and too much. The situation is as valid even to this day and has a ring of historical inevitability. This is just as true of Modern Indian literature and the theatre. In dance the process of modernization is marginal and in music even less. While the artist learnt much from this experience, he had unconsciously entered the race towards a new international concept in art. One might regard this as a typical characteristic of a new-born old nation and part of its initial predicament. Our attitude to life in general, the various approaches to solve an infinite variety of problems are similarly oriented.

A major characteristic of contemporary Indian Painting is that the technique and method have acquired a new significance. Form came to be regarded as separate entity and with its increasing emphasis it subordinated the content in a work of art. This was wholly true until recently and is true somewhat even now. Form was not regarded as a vehicle for content. In fact the position was reverse. And the means, inspired and developed on extraneous elements, rendered technique very complex and brought in its train a new aesthetique. The painter has gained a great deal on the visual and sensory level: particularly in regard to the use of colour, in the concept of design and structure, texture, and in the employment, of unconventional materials. A painting stood or fell in terms of colour, compositional contrivance or sheer texture. Art on the whole acquired an autonomy of its own and the artist an individual status as never before.

On the other hand, we have lost the time-honoured unified concept of art, the modern artistic manifestation having clearly taken a turn where any one of the elements that once made art a wholesome entity now claimed extraordinary attention to the partial or total exclusion of the rest. With the rise of individualism and the consequent isolation of the artist ideologically, there is the new problem of the lack of a real rapport of the artist with the people. The predicament is aggravated by the absence of any appreciable and specific inter-relation between the artist and society. While it may be argued up to a degree that this characteristic predicament of contemporary art is the result of a sociological compulsion, and that present day art is reflective of the chaotic conditions of contemporary society, one cannot but notice the unfortunate hiatus between the artist and society. The impact of horizons beyond one's own has its salutary aspects and singular validity in the light of increasing international spirit of the present times. The easy transport with other peoples and ideas is salutary particularly in respect of technique and material, in the sharing of new ideologies and in investing art and artists with a new status.

Once more, at the end of quarter century of eclecticism and experimentation, there is some evidence of a pent up feeling and of an attempt to retrace and take stock of things. The experience and knowledge, invaluable as it is, is being shifted and assessed. As against the over- bearing, non-descript anomaly of internationalism, there is an attempt to look for an alternative source of inspiration which, while it has to be contemporary may well spring from one's own soil and be in tune with one's environment.

Contemporary Indian art has travelled a long way since the days of Ravi Verma, Abanindranath Tagore and his followers and even Amrita Sher-Gil. Broadly, the pattern followed is this. Almost every artist of note began with one kind of representational or figurative art or the other tinged with impressionism, expressionism or post-expressionism. The irksome relationship of form and content was generally kept at a complementary level. Then through various stages of elimination and simplifications, through cubism, abstraction and a variety of expressionistic trends, the artists reached near non-figurative and totally non-figurative levels. The 'pop' and the 'op', the minimal and anti-art have really not caught the fancy of our artists, except for very minor aberrations. And, having reached the dead and cold abstraction, the only way open is to sit back and reflect. This copy-book pattern has been followed by a great number of artists, including senior and established ones. As a reaction to this journey into nothing, there are three new major trends: projection of the disturbed social unrest and instability with the predicament of man as the main theme; an interest in Indian thought and metaphysics, manifested in the so called 'tantric' paintings and in paintings with symbolical import: and more than these two trends is the new interest in vague surrealist approaches and in fantasy. More important than all this, is the fact that nobody now talks of the conflict between form and content or technique and expression. In fact, and in contradiction to the earlier avowal, almost everybody is certain that technique and form are only important prerequisites to that mysterious something of an idea, message or spirit, that spark of the unfathomable entity that makes such man a little different from the other.

INDIAN THEATRE: INHERITANCE, TRANSITIONS AND FUTURE OPTIONS

The Indian theatre has a tradition going back to at least 5000 years. The earliest book on dramaturgy anywhere in the world was written in India. It was called Natya Shastra, i.e., the grammar or the holy book of theatre by Bharat Muni. Its time has been placed between 2000

B.C. to 4th Century A.D. A long span of time and practice is needed for any art or activity to form its rules and notifications. Therefore, it can be said with assurance that to have a book like Natya Shastra, the Indian theatre must have begun long, long before that if we go back to historical records, excavations and references available in the two great epics The Ramayanaand The Mahabharata .

Theatre in India started as a narrative form, i.e., reciting, singing and dancing becoming integral elements of the theatre. This emphasis on narrative elements made our theatre essentially theatrical right from the beginning. That is why the theatre in India has encompassed all the other forms of literature and fine arts into its physical presentation: Literature, Mime, Music, Dance, Movement, Painting, Sculpture and Architecture - all mixed into one and being called ‘Natya’ or Theatre in English.

Here it can be said that all the ancient traditions in the world - whether Eastern or Western - present almost the same picture of the theatre. On a superficial overview of both the traditions, they may sound similar in their exterior or physical manifestations but if we go deeper into the philosophy and outlook of both the worlds, it will be easier to understand that both of them are poles apart in their basic nature. The western philosophy of life is deep-rooted in the belief that there is no life after death whereas the Indian philosophy, especially the Hindu doctrine, sees life in a continuity, i.e., there is no end even after death.

Life keeps on moving as a circular activity. Theatre in the West presents life as it is whereas in India it presents life as it should be. In other words, this can be explained like this : Life in the West has been portrayed nearer to realism whether in theatre or other arts but in India it has been illustrated more in idealistic terms. This has been so right from the beginnings of the theatre in both the hemispheres.