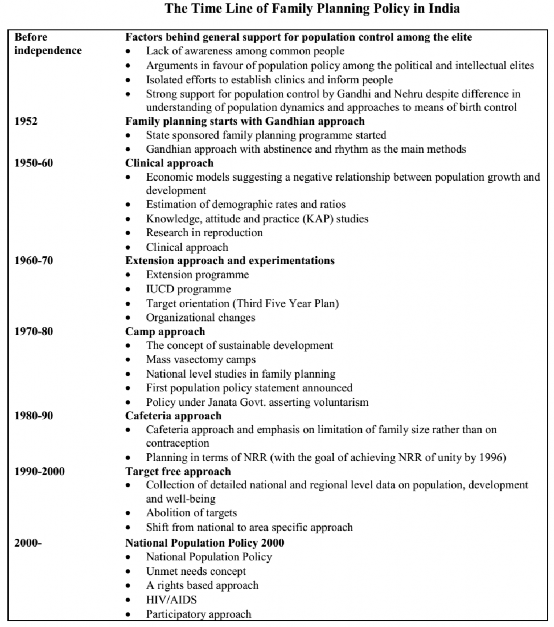

In fact, India was perhaps the first country to explicitly announce such a policy in 1952. The aim of the programme was to reduce birth rates “to stabilize the population at a level consistent with the requirement of national economy”.

The population policy took the concrete form of the National Family Planning Programme. The broad objectives of this programme have remained the same – to try to influence the rate and pattern of population growth in socially desirable directions. In the early days, the most important objective was to slow down the rate of population growth through the promotion of various birth control methods, improve public health standards, and increase public awareness about population and health issues.

The Family Planning Programme suffered a setback during the years of the National Emergency (1975-76). Normal parliamentary and legal procedures were suspended during this time and special laws and ordinances issued directly by the government (without being passed by Parliament) were in force. During this time the government tried to intensify the effort to bring down the growth The Family Planning Programme suffered a setback during the years of the National Emergency (1975-76). Normal parliamentary and legal procedures were suspended during this time and special laws and ordinances issued directly by the government (without being passed by Parliament) were in force.

During this time the government tried to intensify the effort to bring down the growth rate of population by introducing a coercive programme of mass sterilization. Here sterilization refers to medical procedures like vasectomy (for men) and tubectomy (for women) which prevent conception and childbirth. Vast numbers of mostly poor and powerless people were forcibly sterilized and there was massive pressure on lower level government officials (like school teachers or office workers) to bring people for sterilization in the camps that were organized for this purpose. There was widespread popular opposition to this programme, and the new government elected after the Emergency abandoned it.

The National Family Planning Programme was renamed as the National Family Welfare Programme after the Emergency, and coercive methods were no longer used. The programme now has a broad-based set of socio-demographic objectives. A new set of guidelines were formulated as part of the National Population Policy of the year 2000.

9.1. National Population Policy 2000

The National Population Policy 2000 has made a qualitative departure in its approach to population issues. It does

not directly lay emphasis on population control. It states that the objective of economic and social development is to improve the quality of lives that people lead, to enhance their well-being, and to provide the opportunities and choices to become productive assets (resources) in the society. Stabilizing population is an essential requirement for promoting sustainable development. The immediate objective of the NPP 2000 is to address the unmet needs for contraception, health care infrastructure, and health personnel, and to provide integrated service delivery for basic reproductive and

child health care. The medium term objective is to bring the total fertility rate (TFR) to replacement levels by 2010 through vigorous implementation of inter-sectoral operational

strategies. The long term objective is to achieve a stable population by 2045 with sustainable economic growth, social development, and environmental protection.

Total Fertility Rate at Replacement Level: It is the total fertility rate at which newborn girls would have an average of exactly one daughter over their lifetimes. In more familiar terms, every woman has as many babies as needed to replace her. It results into zero population growth.

Stable Population: A population where fertility and mortality are constant over a period of time. This type of population will show an unvarying age distribution and will grow at a constant rate. Where fertility and mortality are equal, the stable population is stationary.

The history of India’s National Family Welfare Programme teaches us that while the state can do a lot to try and create the conditions for demographic change, most demographic variables (especially those related to human fertility) are ultimately matters of economic, social and cultural change.