Vaishali is keen on learning classical music. But her teacher lives far from where Vaishali lives. Her father is also making her work in the family business. He is also insisting that she should continue with her post graduation. Vaishali is caught in the conflict between her love for classical music and her other engagements. She decides to reduce her teaching sessions by half.

What is the psychological concept which Vaishali’s behaviour illustrates?

1. She is showing excessive dependence on her father and is allowing herself to be dictated by him.

2. Shehas no genuineinterest in classical music.

3. She has too many irons in the fire.

4. Through her action, Vaishali has reduced the cognitive dissonance she was experiencing.

The first answer choice is inappropriate. There is no reason to believe that she is over-dependent on her father. His advice to her on pursuing post graduation and learning about family business is sensible.

The second answer choice can be rejected since Vaishali has not given up learning classical music in spite of her other pressing commitments.

The third alternative is a general observation. In fact, we have to pursue several tasks and perform many roles simultaneously in life. This is a common situation. Multitasking skills are needed in life and in professions.

The fourth answer choice correctly explains the psychological rationale of Vaishali’s decision. She is pursuing divergent tasks demanding her time and effort. All the tasks are important. But the pull of tasks in different directions and time pressure are creating a situation of cognitivedissonance for her. This leads to mental tension. She has overcome the cognitive tension by striking a balance between the time allotted for different tasks. Her decision can be conceptualized in non-psychological terms also. In that case, one speaks of the relative priorities she should attach to the different tasks she is pursuing.

As mentionedearlier,governmentssometimes want to changethetraditional beliefs and attitudesof people. This is connected with efforts towards modernization. Conservative beliefs and behaviour could hinder development and social change. Thus people may resist family planning, refuse to send their girls to school or fail to adopt new agricultural technologies. Then how can government induce people to adopt new attitudes and undertake actions that promote economic development? The emphasis on attitudes often arises from the view that they lead to concomitant actions.

Surprisingly, this common sense viewed no support from empirical studies. In fact, early psychologists took it for granted that attitudes of people govern their behaviour. This view appeared doubtful as a result of two famous studies. The first study showed that people do not behave according to their stated attitudes. In the early 1930s, LaPiere accompanied a young Chinese couple during their travel in USA, and observed whether they faced any racial prejudice in motels, restaurants or hotels. It may be noted that Chinese faced discrimination in USA at that time. He found that they were well-treated. Later he sent a questionnaire to these very establishments asking whether they would welcome Chinese guests. Surprisingly, most of the respondents said that Chinese are unwelcome. Thus, though the establishments treated the Chinese well, they expressed a different attitude in the questionnaire. In other words, people did not behave according to their stated attitudes.

The second study was made by Corey. At the start of the semester, Corey devised a measure of the attitude of students towards cheating in the examination. The measure indicated that the students were inclined to copy in the examinations. During the semester, he took many tests, and allowed ample scope for students to cheat in the tests. Here again, the conclusion was negative. Although the students said that they were willing to cheat in examinations, they did not in fact do so. Subsequent empirical studies confirmed that attitudes did not result in behaviour consonant with them. One social psychologist Wicker in fact suggested that the concept or construct attitude is a worthless research tool and should be abandoned.

In the meanwhile, social psychologists began developing reliable measures to study attitudes. Researchers also started studying the processes of attitude formation and attitude change. We discussed these two topics in the previous sections. Further, American army’s use of films and mass media during the Second World War, spurred interest in communication and persuasion. Notwithstanding

findings to the contrary, the users of communication theories relied on the assumption that change in attitudes wouldalterbehaviour.

Faced withtheevidenceabouttheattitude–behaviourinconsistency,someresearchersdoubtedthe validity of survey procedures and the suitability of the samples. Some scholars argued that the persons included in the sample and covered in the survey were unrepresentative of the general population. Doubts were expressed about the verbal attitude measures (or what the people surveyed said). The individuals covered in the survey showed a response bias; to questionnaires which tried to discover their attitudes and personality traits, they gave replies which carry social approval. (They tried to be goody-goody.)Theyconcealedtheirtruefeelings.Nobodywants to givetheimpressionofbeingnasty!

To get over such problems, researchers adopted disguised verbal procedures camouflaging the true purpose of the instrument or the questionnaire. Another procedure relied on physiological reactions like heart rate, palmar sweat and galvanic skin response. However, both the procedures proved unsatisfactory.

Researchers also tried another approach. Attitudes measurement techniques then in use, generated with a single score representing the respondent’s overall positive or negative reaction to the attitude object. Many theorists felt that attitude measures reflected only one of the three components of behaviour. Most of the time, the attitude measure was based only on the affective or emotional component and left out the cognitive and conative or behavioural components. Attempts were then made to build measures covering the three components. However, the three-component approach failed to explain the attitude-behaviour inconsistencies.

In their studies, investigators examined two kinds of inconsistency and explored various possibilities One approach relied on refining surveys and investigative procedures. Another approach looked at reasons which prevented people from acting fully in line with their activities. Social psychologists also explored situations which showed a better fit between attitudes and behaviours. They propounded theories incorporating additional explanatory variables. We will briefly outline these approaches. One type of inconsistency consists in people (in psychological terminology) failing to act according to their declared behavioural intentions. In simple language, during a survey, they would tell the investigator that they would do X (general symbol for act or behaviour) or not do X. But in practice, they would do its opposite (or not do anything).

Psychologists use questionnaires or surveys to discover the general (evaluative) attitudes of people toward any chosen object of their behaviour. They believe that favourable attitudes will elicit positive responses to the object and unfavourable attitudes will elicit negative responses. Inconsistency arises when the general attitude fails to correlate with the specific behaviour under investigation. This is called evaluative inconsistency because the evaluation expressed in verbal attitudes (or what is said) does not match with actual behaviour.

Most instances of attitude behaviour inconsistency fall into this category. To visualize the problem, we need to think of: (a) the general attitude; (b) the person, group, thing or event towards which attitude is directed i.e. object of the attitude; and (c) a specific behaviour towards the object of attitude. The inconsistency is that (a) does not lead to (c). An example can be of a person who says that he is deeply religious, but does not visit temples.

Evaluative inconsistency arises from the complenxity of relation between general attitude and individual behaviour.

Attitude and behaviour; according to some researchers, diverge due to certain moderating factors. These are connected with (a) traits of the individual performing the behaviour, (b) the situation in which it is performed; and (c) the characteristics of the attitudeitself. As regards differences between individuals, researchers refer to three individual difference variables: self-monitoring tendency, self- consciousness or self-awareness, and the need for cognition.

(a) Individuals high in self-monitoring speak or act appropriately depending on the social or interpersonal context of a situation. They tailor their true attitudes to situational requirements. They hide their true feelings. But individuals who are not very self-conscious say or do things that truly reflect their own attitudes, traits, feelings, and other current inner states. They show greater attitude-behaviour consistency. Further, people are likely to act according to their attitudes if they have vested interest in a topic or if they are confident of their attitudes or if they regard the attitude object as important.

(b) The situational moderators of the attitude-behaviour relation include time pressure and presence or absence of a mirror in the behavioural situation. Time pressure forces one to think quickly. Introduction of a mirror increases the subject’s self-awareness. Both the factors lead to greater correspondence between general attitude and specific behaviour.

(c) As for qualities of the attitude that may moderate the strength of the attitude-behaviour relation, investigators examined three aspects. First aspect is the degree of consistency between the cognitiveand affective components of the attitude. If thetwo are correlated, behaviour tends to follow attitude. Secondly, behaviour tends to follow attitudes when they are based on direct experience as opposed to second-hand information. Attitude formed as a result of central processing [route] is more likely to lead to corresponding behaviour than if it is formed through peripheral processing. As we saw before, in central processing, information is closely scrutinized for its logical validity and factual veracity. In peripheral processing, the participant does not subject the information to rigorous scrutiny.

Domain of Interest and Set of Behaviour

Above mentioned moderators partly explain attitude-behaviour divergence. However, social psychologists would like to predict accurately from an individual’s general attitude his individual behavioursor actions.On one sideis an individual’sattitude;on theotherare hisindividualbehaviours expected to flowfrom his attitude. Thelattersometimes do not materialisebecausegeneral attitudes can manifest in numerous ways. While some may result from it, others do not follow as anticipated

For example, ‘religiosity’ is a general attitude. A specific, single behaviour may not follow from it. An avowedly religious person may not regularly visit temples. However, he may be attending bhajans, listening to religious discourses on TV, reading religious treatises and practising meditation. We canlist several similarreligiousactivities.It will be foundthat a set or group of individual religious acts will together reflect his religiosity.

What this shows is that if we exhaustively enumerate all the individual behaviours which flow from an attitude, we can predict that an individual with those attitude will display some of the associated individual behaviours. However, we are often interested not in a broad multiple act index of behaviour, but with predicting when specific individual behaviours occur. We want to know the factors which lead to the individual behaviours of interest to us.

Let us consider Swachh Bharat programme in a village in Saurashtra. How can we predict the response of a poor village household to it? Now, women in rural Saurastra have very positive attitude to cleanliness. Even in small houses, the single living room is kept clean; the meagre furniture and articles are kept in neat and tidy order. The kitchen is spic and span with a row of gleaming copper vessels.

However, this general attitude towards cleanliness could be insufficient to elicit the individual behaviours needed for Swachh Bharat programme. While the interior of the house is spotlessly clean, its surrounding public area is neglected. People may prefer to continue with the old habit of answering nature calls in public. They may be reluctant for want of resources to invest in private toilets. At the same time, before visiting officers canvassing the programme, they will welcome it.

The challenge is how to convert the attitude into appropriate individual behaviours. Similarly, people may express general concern for environment. But often this is not followed by individual behaviourssuch as conservingwater, reducingelectricityconsumption or recycling wastes.

The problem for administrators is often to induce people to act in particular desirable ways based on general attitudes. Another way of looking at the problem is: When are people likely to act according to their attitude? Social psychologists give partly theoretical answers. We try to express them in practical terms.

A single behaviour consists of an action directed against a target, performed in a context, and at a certain point of time. An officer may be interested in knowing why villagers may or may not join (action) Swachh Bharat programme (target) their village (context) at a point of time (non agricultural season). Here, we explicitly stated the four elements. If one wants to ensure compatibility between attitude and individual behaviour, both should contain the same action, target, context and time elements. In this example, the context has to be widely understood including provision of financial assistance, technical advice and supervision for toilet construction and other factors affecting the willingness to join the programme. If the four elements likely to translate attitude into individual behaviour are satisfied, then the programme will get off the ground. In plain language, the constraints acting on people and impeding the desired action have to be removed.

The Mode (Motivation and Opportunity as Determinants) Model

In this model, Fabio explains how people’s attitudes influence their evaluation of people and events. Attitudes bias the manner in which people view and judge information about other people and events. Bias depends on the strength of people’s attitudes.

This model outlines how bias is triggered, and how it operates in two groups of people. The first group consists of intelligent and motivated individuals; the second one consists of less intelligent and motivated individuals. In both the groups, unless the attitude is activated, bias will not occur.

The attitude can be activated in two ways: in a controlled or deliberative manner and in an automatic or spontaneous manner. Intelligent and motivated individuals process information deliberately; less intelligent and less motivated individuals process information spontaneously.

Attitudes have to be readily available in the memory of the second for bias to arise. When motivation and ability to carefully process information are high in individuals, attitudes need not be readily available from memory. They can recall them through mental effort. For other individuals, attitudes have to be present in memory so that they can be activated automatically. In whichever way thegeneral attitudeis activated,it canintroducebias.

Individuals with favourable attitudes are likely to take into account and process the object’s positive attributes. Individuals with unfavourable attitudes toward the object are likely to concentrate on its negative aspects. Although one may harbour prejudice against a caste, he may hide it if the group in which he is placed in a situation opposes casteism. Though perceptions tend to guide behaviour, people will also factor in the likely consequences of acting in line with such perceptions.

Activation of an attitude is more difficult when an individual’s motivation or cognitive capacity is low than when it is high because the individual cannot retrieve or construct it easily. However, attitudes will be available if they are automatically activated. In the spontaneous processing mode, weak attitudes will not be activated and will, thus, not be available to bias the definition of the event or guide behaviour.

Thus, automatic or spontaneous activation takes place when attitudes are strong. Attitude is defined in this context as a learned association in memory, between an object and a positive or negative evaluation of that object, and attitude strength is equivalent to the strength of this association. Automatic attitude activation occurs when a strong link has been established in memory between the attitude-object and a positive or negative evaluation. The stronger the attitude, the more likely it is that it will be automatically activated and, hence, be chronically accessible from memory. Further, due to a biased perception/interpretation of information, strong attitudes are more likely to be resistant to change than weak attitudes. This is consistent with the general view that strong attitudes involve issues of personal relevance and are held with great conviction or certainty. As a result, they are assumed to be persistent over time and be resistant to attack, to influence perceptions and judgments, and to guide overt behaviour.

If one is a right wing thinker but is working in civil service, his prejudices may get pushed back due to work pressure and the time he spends with colleagues. But if he happens to read an article written with a leftist slant or a policy proposal with mild leftist flavour, he will not overlook the leftist overtones of the two. His intelligence and motivation will operate to trigger his ideological attitude. But a less intelligent or motivated individual will miss out ideological nuances in the two.

Many theorists regard that the nearest cognitive antecedent of actual behavioural performance is the agent’s intention than his attitude. It means that one can accurately predict specific behaviours

from the intentions of their performers. Many studies have substantiated the predictive validity of behavioural intentions.

There is an important difference between performing behaviour and attaining a goal. Behaviour is within one’s control. But goal achievement depends also on extraneous factors. One may exercise and regulate diet (behaviour) to lose weight (goal).But weight loss also depends on physiological conditions beyond one’s control. Intentions are immediate antecedents of behaviour. When people feel that a goal depends on many factors beyond their control, they may refuse to act. Or the intention fails to produce the expected behaviour.

We may notetwo other aspectsconcerningintentionsandbehaviour.One is that intentionshave to remain stable if they are to produce the expected behaviour. The intentions which investigators record tend to change with passage of time. Secondly, there has to be compatibility between the measures of intention and of behaviour. For instance, a question whether X intends to exercise in future does not have a compatible behaviour measure. But the question whether X will walk four times a week in the coming eight weeks will elicit an answer which is likely to match X’s exercise behaviour.

We will now discuss the theory of reasoned action. These theories go beyond prediction of likely behaviour; they discuss factorsthat lead to formation of intentions.

The decision to adopt a particular behaviour will be determined by:

(i) positive or negative consequences of behaviour;

(ii) approval or disapproval of behaviour by respected individuals or groups; and

(iii) factors that may facilitate or impede behaviour.

Positive or negative consequences of behaviour are also known as behavioural beliefs, or outcome expectations, and costs and benefits. An individual will have a favourable attitude towards a particular behaviour if its perceived benefits outweigh its costs. If the perceived benefits are less than the costs, he will have an unfavourable attitude.

Normative beliefs refer to the likely approval or disapproval of a particular behaviour by family, friends, colleagues and such others. They create a social pressure or norm to engage in or to avoid the behaviour. When respected persons or groups expect a particular behaviour or disapprove of it,the pressureinfluences behaviour either positively or negatively. Similarsocial pressuresoperate when respected individuals or groups (nowadays called ‘role models’) adopt a particular behaviour or shunit.

Control beliefs are determined by perceived factors which help or hinder the performance of behaviour. They lead to the belief that one has or does not have the capacity to perform the behaviour. Control beliefs denote self-efficacy and personal agency or perceived behaviour control. Self-efficacy arises from feeling that one has the skills and resources needed for completing a task. Behavioural control means the factors within his/her control which determine success or failure.

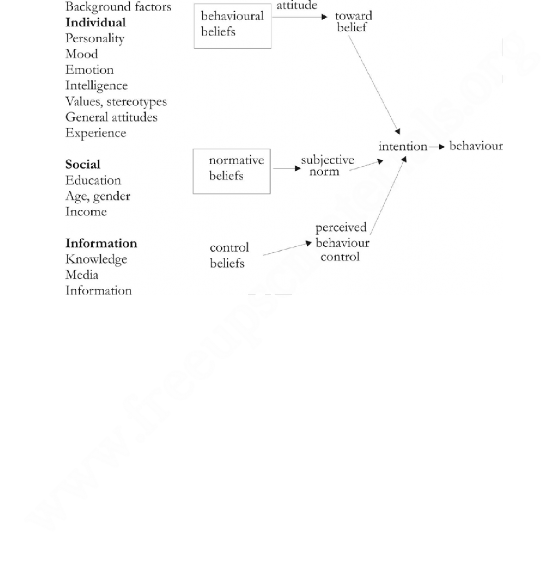

The reasoned action model is schematically depicted below.

The following diagram will helpstudents followthe terms used in the theoryand their connections. Obviously, there will be not time or space for reproducing it (even if a question on it appears) in

the answer. But the diagram shows how behaviour can be traced back to intention immediately preceding it. Intention is worked backwards to three components of attitude which in turn are linked to belief. Finally, many background factors influence these intervening variables leading to behaviour. Students can use this broad perspective in many contexts.

The background factors are individual, social and informative. They lead to formation of beliefs covering behaviour, norms and control. These create attitudes toward belief, norms and perceived behaviour control. These in turn lead to intention and action.

This model assumes:

1. Intention is the immediate antecedent of actual behaviour.

2. Intention, in turn, is determined by attitude toward the behaviour, subjective norm, and perceived behavioural control.

3. These determinants are themselves a function, respectively, of underlying behavioural, normative, and control beliefs.

4. Behavioural, normative, and control beliefs can vary as a function of a wide range of background factors.

These beliefs need not be true; may be inaccurate, biased, or even irrational. However, once a set of beliefs is formed, it provides the cognitive foundation from which attitudes, perceived social norms, and perceptions of control and ultimately intentions are assumed to follow in a reasonable and consistent fashion.

The behavioural, normative, and control beliefs people hold about performance of a given behaviour are influenced by a wide variety of cultural, personal, and situational factors. Thus, we may find differences in beliefs between men and women, young and old, Black and White, educated and uneducated, rich and poor, dominant and submissive, shy and outgoing, and between individuals who have an individualistic orientation and those who have a collectivistic orientation. In addition,

they may be affected by the physical environment, the social environment, exposure to information, as well as such broad dispositions as values and prejudices.